Here is a startling fact with profound implications: Nearly 60% of the 911 ambulance calls in most major US cities are related to dysfunctional breathing habits. And the most common dysfunctional breathing habit is by far, hyperventilation. In other words: “over-breathing.”

And despite all the hype you may have heard about “deep breathing to super-oxygenate” your cells, the fact is: almost anyone can reduce the supply of oxygen to their brain by more than 40% in less than one minute, simply by hyperventilating.

Over-breathing is not about taking in too much oxygen: it’s about blowing off too much carbon dioxide. CO2 is a powerful vasodilator. That means it relaxes or expands micro vessels, setting the stage for O2 delivery. Carbon dioxide is also a volatile acid, which means it profoundly affects your pH level.

Effects of Overbreathing on Cerebral O2

Effects of Overbreathing on Cerebral O2

Due to Vasoconstriction

Reduction of O2 Availability by 40%

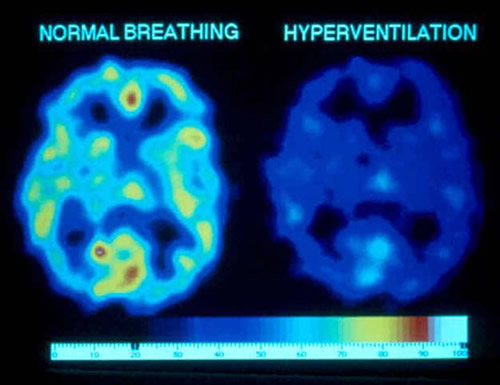

Red/yellow/pale blue = most O2

Dark blue = least O2

In this image, oxygen availability in the brain is reduced by 40% as a result of about a minute of over-breathing (hyperventilation). Not only is oxygen availability reduced, but glucose critical to brain functioning is also markedly reduced as a result of cerebral vasoconstriction.*

Breathing and respiration are different. Breathing is a learned behavior. It refers to what you do in order to move air in and out of the lungs. Respiration on the other hand is a chemical process, regulated by O2 requirements, CO2 levels, and body fluid pH levels.

Breathing varies and changes constantly depending on our mood, our posture, what we are doing, what we are wearing, how we are feeling, what we are thinking. We alter it when we laugh, cry, sing, speak, listen, work, think, and move.

The way you breathe (consciously or unconsciously) on a moment-to-moment basis is either supporting or interfering with your respiration, and so it is profoundly affecting your health and wellbeing in ways you may have never imagined.

Here is a quick list of some of symptoms and conditions that over-breathing can cause:

-

Shortness of breath, feelings of suffocation, dry mouth

-

Chest pains, heart palpitations, high blood pressure

-

Sweaty palms, cold hands, numbness and tingling

-

Trembling, twitching, muscle spasms, headaches

-

Anxiety, panic attacks, and emotional outbursts

-

Stress, physical tension, weakness and fatigue

-

Dizziness, fainting, blurred vision, black-outs

-

Nausea, abdominal cramps and bloatedness

In addition to disturbing your acid-base balance and triggering the constriction of blood and bronchial vessels, over-breathing disturbs the body’s electrolyte balance (bicarbonates, calcium, sodium, potassium). Over-breathing compromises cognitive function, including awareness and perception, memory, learning, and problem solving.

It compromises cardiac function, causing cardiac arrhythmias. It compromises muscle function and nervous system function. Over-breathing can trigger, exacerbate or perpetuate existing conditions like asthma, epilepsy, seizures, irritable bowel, ADHD, chronic fatigue, anxiety disorders, and much more.

The habit of over-breathing, like most habits, is formed unconsciously, in response to physical, psychological, emotional, and social challenges. And it often developsas a way to disassociate or disconnect from memories we don’t like, or to avoid feelings we don’t want to have. Over-breathing becomes a primary coping strategy with major payoffs.

In effect, we become the victims of our own poor breathing habits, and we attribute the consequences of those habits to other causes.

Medical doctors routinely order expensive and invasive medical tests when presented with “unexplained symptoms.” And when no physical abnormalities can be found, they prescribe mood altering psychiatric drugs. Meanwhile the real problem—dysfunctional breathing—goes unrecognized and remains unaddressed.

In order to identify and correct poor breathing habits, you have to identify the triggers. You have to connect the symptoms to the habits. You have to uncover the motivations behind the habits, and identify the reinforcements and the “payoffs.”

In order to accurately assess your respiration on a moment-to-moment basis, a capnometer may be required. A capnometer is a simple device used to measure the carbon dioxide in the air you exhale. From that, the CO2 level in your lungs, blood, and body fluids can be inferred.

How do you know if you are over-breathing?

Studies indicate that the vast majority of people are over-breathing to some extent. You may be breathing perfectly most of the time, and only slip into dysfunctional breathing when performing certain tasks, when confronted with certain situations, during certain interactions, with certain people, etc.

A simple easy and surprisingly accurate test for over-breathing is to measure your comfortable pause after the exhale. Take in a normal breath, let it out, and then block your nose, close your mouth and wait. Don’t breathe in. Time yourself.

Sitting relaxed and at rest, you should be able to comfortably tolerate a pause of at least 30 seconds. In other words, you should have no strong urge to breathe, and you should not feel any apprehension, anxiety, or discomfort.

Note: If you have to take a big “recovery breath” or you find yourself breathing several big or quick breaths after the pause, you have held your breath too long, and over-extended a comfortable pause.

What can you do about over-breathing?

Practice breath awareness; practice relaxation techniques; and learn slow diaphragmatic breathing so that you can interrupt over-breathing when it begins to happen.

Stop getting in the way of your body’s natural respiratory reflexes. Learn to “allow” the breath instead of “forcing” the breath.

Focus on the transition point between your exhaleand your inhale. Postpone the inhale for a few seconds at that point, and notice what you feel. If you feel a subtle discomfort, you will unconsciously grasp for the next inhale. This will eliminate the anxiety, but it will block the natural respiratory reflex.

Practice lengthening the pause after the exhale in order to desensitize yourself to that subtle feeling of apprehension. Learn to trust that pause. Visualize something positive during the pause. Turn it into a comfort zone. Make it a meditation.

A good general practice is to use the 1-2 formula. That is you exhale should be twice as long as your inhale. You could inhale for the count of 2 and exhale for the count of 4. You could breathe in for the count of 3 and breathe out for the count of 6. Breathe in 4 and breathe out 8.

If this becomes easy for you, you could graduate to an advanced practice: 1-3 or 1-4. That is your exhale is three times longer than the inhale, or 4 times longer. For example, breathe in for 2 and breathe out for 6; breathe in for 2 and breathe out for 8.

There are many specific remedial breathing exercises and techniques that you can learn. The best advice is to attend a breathwork seminar or training. Get some personal coaching or guidance. You could schedule a Skype consultation with me.

I encourage you to become a Breath Mastery Inner Circle Member, and then you can access all the training materials for free. For information on this, Visit: www.breathmastery.com.

Special Note:

If you are a healthcare practitioner, a holistic healer, a human service professional, a performance coach, a consultant, or educator, or a breathworker, you may be interested in the MS Degree Program in Applied Breathing Science, offered by my colleague and “CO2 Guru” Dr. Peter Litchfield*.

Go to: http://www.breathmastery.com/ms-program/

Dan Brulé has studied and practiced breathwork with more than 80,000 people in over 40 countries since 1976. His travel and teaching schedule is posted at www.breathmastery.com.

Post new comment

Please Register or Login to post new comment.